I was doing a hike at one of the NJ parks a week or so back when I happened to see a grass that was growing from between the branched fork of a now leafless tree.

The grass looked quite happy and healthy, and a quick look at its base showed some accumulated debris, and perhaps even soil. I can only surmise that it got to its present location via a wind blown seed being deposited in between the trunks.

This of course made me wonder why there didn't seem to be any obligate epiphytic grasses.

Epiphytes are plants that spend part of their lives growing on other plants. They use their host for support but do not depend on them for nutrition or water (unlike parasites), and the main reason for becoming an epiphyte in forested areas is somewhat obvious. By growing high up (perhaps even all the way to the top of the canopy), the plant will have access to light that it would not have growing in the soil.

But the environment for such adventurous species is not a benign one, with the lack of access to soil nutrients and water being the main reasons why not all plants have evolved to take advantage of this lifestyle. Those that did have a variety of morphological and physiological adaptations that allow them to flourish far above the dark forest floor. For example, some orchids have fat pseudobulbs and tubers where they store water and carbohydrates in anticipation of the periodic times when the environment dries out. Their roots are also highly modified so they are able to hold tightly onto trunks and absorb moisture very rapidly using a sponge-like layer called the velamen.

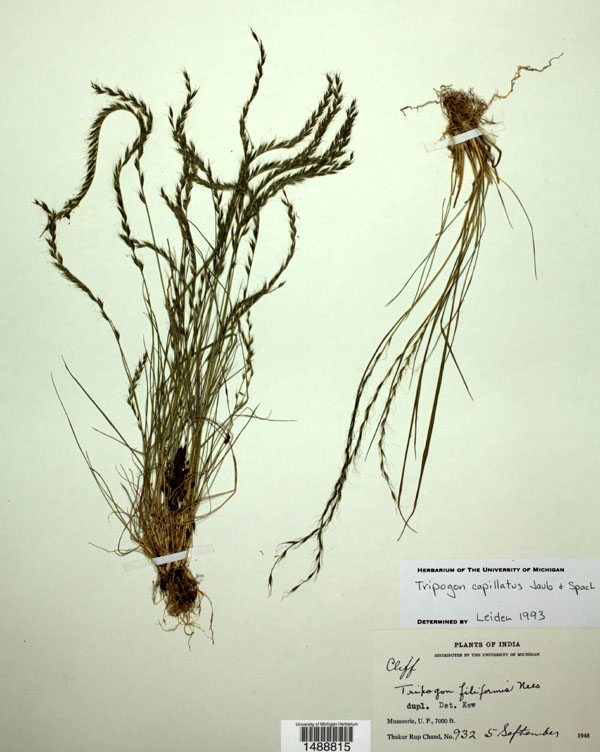

Tripogon capillatus grows as epiphytes on the basal parts of tree trunks in humid evergreen forest, and thus has the distinction of being one of that rarest of grasses - an epiphyte! It is part of a group that seems primed for the epiphytic lifestyle. Tripogon is a small genus with only around 50 species, and many of its members prefer to grow on cliffs of moist rocks, wet granitic boulders and rocky slopes, while others can live in xeric to dry habitats (Thoiba and Pradeep, 2020). Some of the species in that genus are even so-called Resurrection plants - able to revive after being completely dried out!

So why aren't there more epiphytic grasses?

|

| Epiphytes. (c) Hans Hillewaert - Wikipedia |

Even with all these obstacles, a lot of species have made the leap to an epiphytic lifestyle. Epiphytes are not exactly rare, with about 10% of all vascular plants being epiphytic, and with the majority of cases being in the wet tropics. More than 70% of all orchids for example are epiphytic (Atwood JT, 1986), and so are more than 50% of bromeliads (Zotz, 2013).

The Poaceae number more than 11,000 species, and so when I first tried to find examples of epiphytic grasses, I expected quite a number to be living la vida loca, so to speak, high up above where the lighting is good. Instead, the literature turned up...

...a grand total of ONE (perhaps TWO) species of grasses that have been declared epiphytes!

|

| Tripogon capillatus (c) GBIF, specimen from University of Michigan |

A second possible grass epiphyte is Axonopus compressus, which was discovered as isolated individuals (n=3) in the lower and middle layers of two trees in Nigeria (Obalum, 2018). But neither species is beholden completely to this tree-living lifestyle. They are instead likely facultative (or accidental) epiphytes, and able to grow in many types of environment.

Why is a family that is more widespread than any other plant family - one that has members that exist in the coldest, the driest, the hottest, the highest environments - why hasn't it evolved a plethora of tree-living, canopy-dwelling species?

I've been thinking about this, and I think it all boils down to the fact that all grasses are primarily wind-pollinated. It turns out wind pollination is generally uncommon in the wet humid forests where epiphytes are mostly found, and according to at least one source, there have been no reports of any epiphyte that sheds wind-borne pollen (Lowman and Rinker, 2004).

But who really knows? Perhaps there is some other explanation(s) as to why what many consider the most ecologically successful plant family in the world cannot seem to also conquer the tree canopies.

Literature Cited

Atwood, John T. “THE SIZE OF THE ORCHIDACEAE AND THE SYSTEMATIC DISTRIBUTION OF EPIPHYTIC ORCHIDS.” Selbyana, vol. 9, no. 1, 1986, pp. 171–186. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41888801.

Lowman, M.D. & Rinker, H. Bruce. (2004). Forest Canopies: Second Edition.

Obalum, Sunday (2018). Diversity and spatial distribution of epiphytic flora associated with four tree species of partially disturbed ecosystem in tropical rainforest zone. Agro-Science v17: 46-53

Thoiba, K and Pradeep, AK (). A revision of Tripogon (Poaceae: Chloridoideae) in India. Rheedea - Journal of the Indian Association for Angiosperm Taxonomy. Vol. 30(2): 270–277

Zotz, Gerhard (2013). The systematic distribution of vascular epiphytes – a critical update. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 171(3):453-481

No comments:

Post a Comment