Summary: It's a fantastic mobile app that went far beyond my expectations, and would be a great help for anyone who wants to learn about grasses in the southern part of Africa.

My first experience with a mobile app for grasses was for the grasses of Montana, and I found it useful and quite portable, since I brought my phone everywhere.

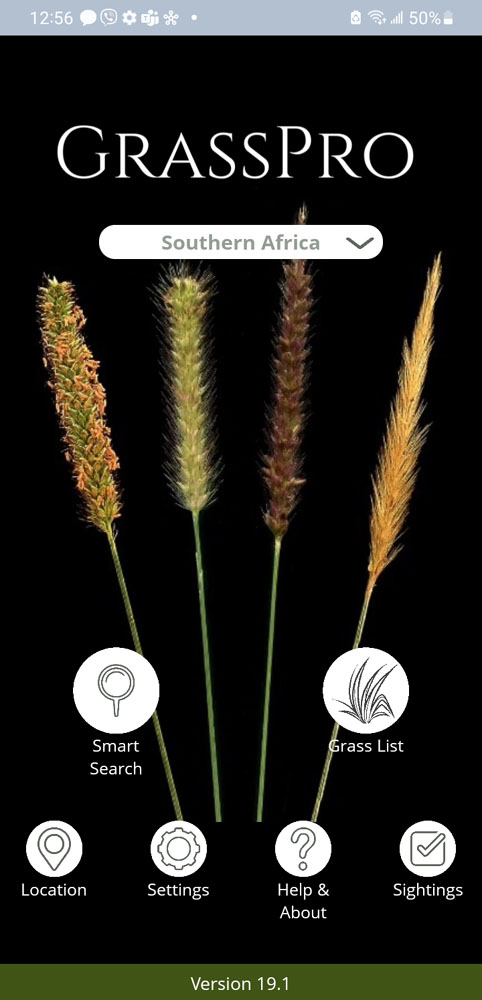

So when I heard about a new app called Grass Pro SA that focused on South African grasses, I immediately downloaded it from the Google PlayStore for my Samsung Android smartphone, and was immediately appreciative of its quality.

The home screen has a rotating background of very nice images of various grass inflorescence, and displays all the main sections of the app.

The Grass List is simply a long list of all the species in the app (there were 324 species when I tested it, but I assume they add to it over time), with the capability to search for specific species by name. The subsections within it contain more detailed info on each species, including nice images, the distribution, and personal sightings. More about this features later below.

|

| Grass List |

The Sightings section allows the user to submit and sync sightings of species that they find to the common database. This is a great feature that is not in the more basic Montana app, and allows users to participate actively in the building of the database.

Help and About gives very detailed information about using the app, as well as credits to those people responsible for its creation.

The Settings section is interesting, because it allows you set the language options for the species and common names. It was cool to be able to see what the common name of Imperata cylindrica is in Afrikaans for example (Donsgras), although most of the African common names seem to be missing (I tried Zulu and Xhosa).

|

| Settings Section |

The Location Section is one of the best features of the app, and it is not available in the free evaluation version. In the main page you can select whether you want to see grasses in your current location (I assume the app uses the phone GPS), from a selected area in a map, or whether you want to see all grasses in South Africa.

|

| Location Main Page |

I decided to try out the

Select from map subsection. As you can see from the image below I selected an area in the southwest corner of Namibia (by just tapping at it), and the app immediately noted that it has records of 20 grass species in that area.

|

| Finding species in a specific map location |

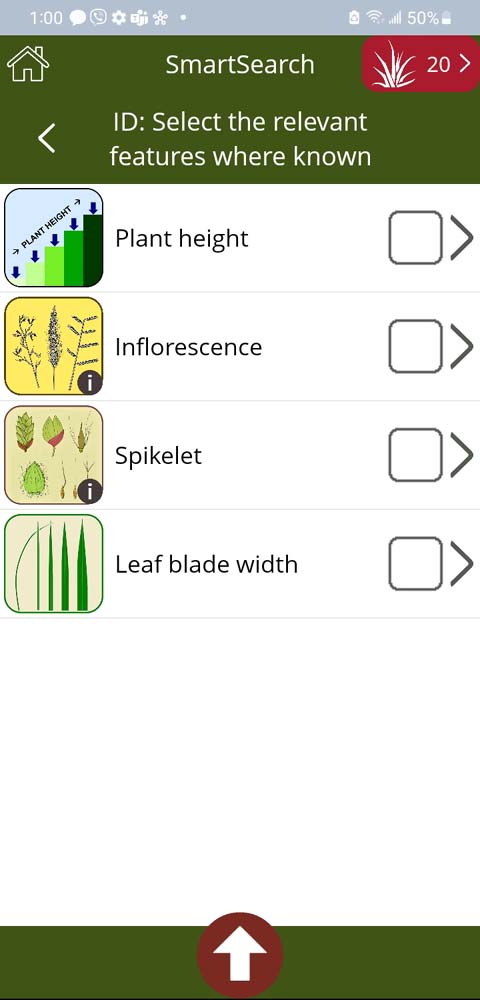

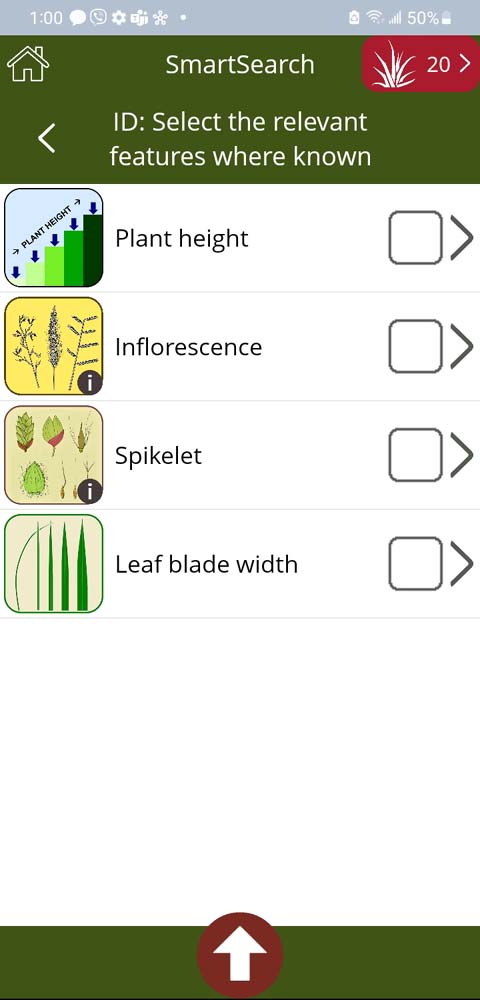

I then tapped the search icon next to the label "20 grasses", and it brought me to a page where I was able to filter the results by specifying particular traits (see image below). The app allowed filtering using 8 different methods, and this was something that was really amazing to me.

|

| Ability to filter results via 8 methods |

Not only can you filter via the usual structural traits, but you can also filter using such unusual ways as ecological information (grazing value, plant succession stage. ecological grazing status, weeds), and even via common uses! (see image below).

|

| Filtering via common uses |

Just to show how the process works, I went the route of using the major physical attributes to identity a specimen.

In this case, I got the option of filtering the 20 species using such features as plant height, inflorescence, spikelet, and leaf blade width (see image below).

|

| Filtering using major or main plant features |

I decided to go with inflorescence, and tapping it took me to another subpage, where I was able to select from various types, such as unbranched, panicle, and digitate flower spikes (see image below).

|

| Selecting type of inflorescence |

A small icon ("i") next to each image allowed me to go to a help and information page that went into detail about the inflorescence types, which was really helpful.

|

| Info page about inflorescence types |

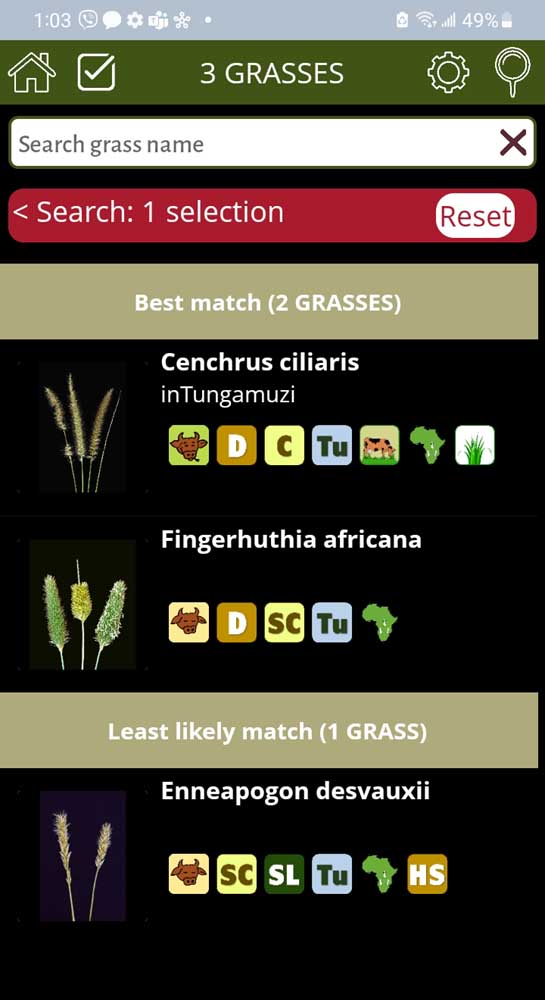

After selecting unbranched, rounded inflorescence, I was taken to a list of 3 grasses that met my criteria.

Since I knew the species

Cenchrus ciliaris, I picked that, and I was taken to a species profile page (see image below). This page not only contained full descriptions of

C.ciliaris, but it also had several nice photographs showing the habit and fine detail of the species. In addition, it also displayed the full distribution of the species in southern Africa.

I cannot emphasize enough how cool this little mobile app was. It went far beyond my expectations, and a lot of work and effort must have gone into creating it. I highly recommend it for anyone who would like to identify and learn about the Poaceae in the southern part of Africa, and I hope similar apps are created for other regions of the world.

I think my only minor gripe is that a lot of the African languages did not seem to have common names for the species, but both Afrikaans and English common names were included. The app was also a bit confusing when I used Current Location to try to see species near me. Since I am located in the USA, I thought that it would note down zero grass species nearby, but it seemed to indicate the presence of all 324 species.

The evaluation version is free, but to see all the species in the database (324 species when I tested it), and be able to use the Location feature, the cost is an annual subscription of around US $10 (including tax).