|

| Wispy inflorescence of Ventenata dubia in foreground |

In an earlier post I discussed how a group of winter annual grasses are spreading like wildfire in the vast Sagebrush ecosystem in the western part of the USA.

This armageddon is destroying not only the pristine sagebrush shrubs which are critical to numerous animals like the sage grouse, but it also is significantly lowering the forage value of the land as palatable perennial grasses are replaced by the mostly unpalatable invasives.

In addition to earlier invasives like Bromus tectorum (cheatgrass) and Taeniatherum caput-medusae (medusahead grass), a newer species has been creating problems for land managers.

|

| Distribution of V.dubia (EDDMaps, 2022) |

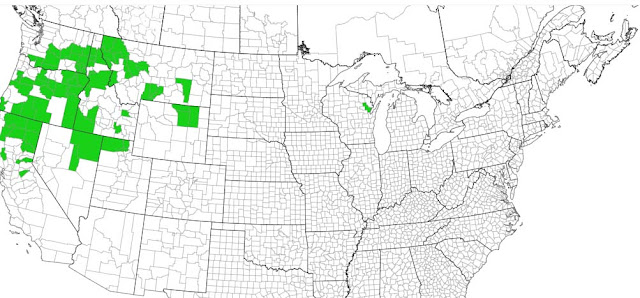

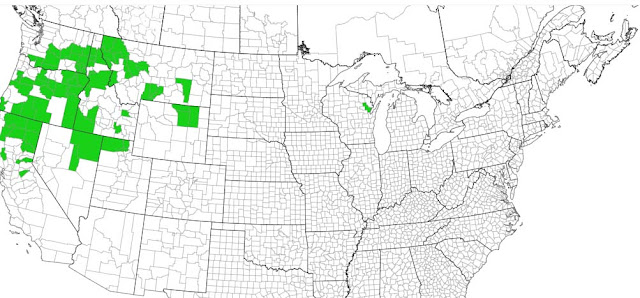

Ventenata dubia was first discovered in Washington State in the early 1950s. It is native to Southern Europe and North Africa, and it has rapidly spread at the rate of 1.2 million hectares per year (Native Invasive Plant Council, 2001), which means an area three times the size of Rhode Island is being invaded every year! It now is found in 11 states and 5 Canadian provinces, and land managers are frantically trying to slow its spread while it is still possible to do so.

|

| Invasion by Ventenata dubia (photo credit: Novak et al) |

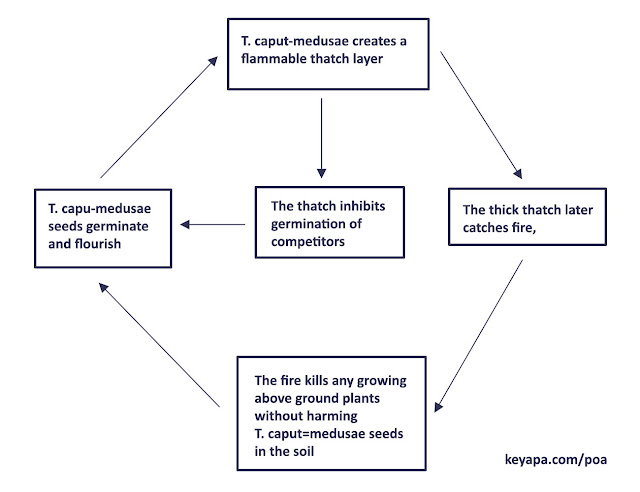

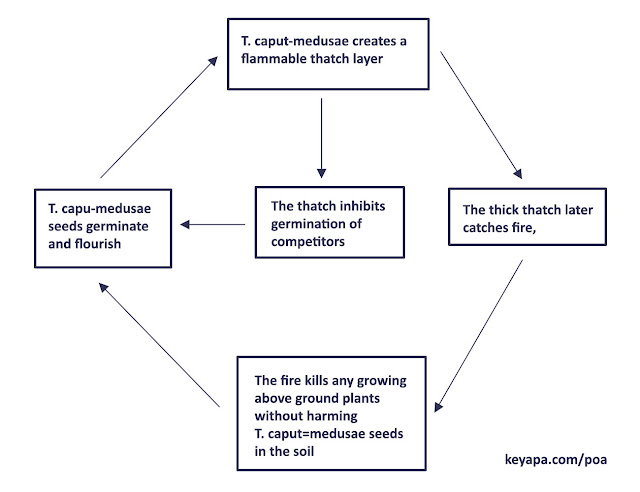

Like other winter annual grasses that have caused havoc in the local ecosystem, V. dubia tends to create a so-called grass-fire cycle, where its presence increases the probability of fires, which in turn removes its competitors and allows it to overran the area. Another way that winter annuals can outcompete other plants is by germinating in fall or early winter, and senescing by mid-summer. This gives it a head start when it comes to taking advantage of the early spring moisture.

|

| The grass-fire cycle of T. caput-medusae |

This species has only recently arrived in Montana, and while botanizing in a local park in the city of Bozeman, I stumbled on a small cluster hidden amongst the other grasses.

On first look, the grass does not exactly inspire dread. Unlike T. caput-medusae with its alien looking inflorescence, or B. tectorum with its multitudes of sharp spear-like awns, V. dubia looks like a puny weakling that would roll over with the smallest puff of wind.

|

| The sharp spear-like awns on B.tectorum is more intimidating than the diffused panicles of V. dubia |

The inflorescence of this species is a spread out panicle, and its thin culm ends at the base with very shallow roots. But its outward appearance belies the heart of a bully. Some studies have shown that invasion by V. dubia in hay fields can result in losses of up to 50% (Prather and Steele, 2009), and like other hegemonic invaders, the diversity of native species suffers when it starts taking hold in an area (Jones et al, 2020).

|

| Ventenata dubia whole plant. Notice weak shallow roots |

Even more frightening is the fact that this new invader seems to be able to successfully dominate habitats that earlier invasives like T. caput-medusae and B. tectorum cannot. In one study researchers found that it had invaded dry forest, woodland, and forest scablands ranging from 1250-1665 m of elevation, places which previously had been relatively immune to winter annual grass invasions. This is important to note, because it means that the spread of this species has increased the overall footprint of invasive annual grasses in the already battered Western USA (Applestein et al, 2022; Tortorelli et al, 2020).

|

| Very long ligule of V. dubia and the remnant dark red color of a node |

I must admit I was lucky in finding the small cluster in that park in Bozeman, MT. The small size of V. dubia and its open diffuse panicles made it hard to distinguish from the masses of other dried grasses that dominated the landscape.

But the specimens I found had panicles with horizontal branches that almost diverged at 90 degree angles, and the spikelets (the structure that holds the grass flowers) on the panicles were restricted to the ends of these branches, both of which are characteristics of the species. A quick check of the ligules (the membrane between the top part of a blade and the culm) also pointed to them as being V. dubia: the species has relatively long and large ligules. The very shallow roots of one specimen that I carefully uprooted is another characteristic of V. dubia, as is the dark nodes that were red earlier in its life cycle.

|

| Dried spikelets of V. dubia with ribbed glumes and lemma with long awns. |

Magnification also offered other clues as to their identity. The dried spikelets had no seeds, but each spikelet had a conspicuous lemma (a bract like structure enclosing a flower) with a protruding awn, and the glumes (the two bracts enclosing the spikelet) were distinctly ribbed along the long axis.

The small infestation that I found may not remain so small, given the nature of V. dubia. But perhaps the much larger grasses around it will contain its spread, or perhaps it will be eradicated after its presence has been reported. Only time will tell.

As a last note, the spread of V. dubia is another major problem in an endangered ecosystem that many people don't even know about. But there is nothing "evil" or even "villainous" about the species, notwithstanding the title of the post. We tend to anthropomorphize other organisms when in the heat of emotion, but this species (like all the other "weedy" plants) is simply doing what it needs to do in order to survive and prosper, with no malice in whatever green heart it has.

Literature Cited

Applestein, C., Germino, M.J. Patterns of post-fire invasion of semiarid shrub-steppe reveals a diversity of invasion niches within an exotic annual grass community. Biol Invasions 24, 741–759 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-021-02669-3

EDDMapS. 2022. Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. The University of Georgia - Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online at http://www.eddmaps.org/; last accessed August 26, 2022.

Jones, L., Davis, C., & Prather, T. (2020). Consequences of Ventenata dubia 30 years postinvasion to bunchgrass communities in the Pacific Northwest. Invasive Plant Science and Management, 13(4), 226-238. doi:10.1017/inp.2020.29

Prather, T. S., and V. Steele. 2009. Ventenata control strategies found for forage producers.

Tortorelli, C, Krawchuk, M, Kerns, B. Expanding the invasion footprint: Ventenata dubia and relationships to wildfire, environment, and plant communities in the Blue Mountains of the Inland Northwest, USA. Appl Veg Sci. 2020; 23: 562– 574. https://doi.org/10.1111/avsc.12511

.jpg)