|

| Olcott Lake in Jepson Prairie Reserve, CA, USA |

I'd like to extend my gratitude to Carol Witham in Sacramento, CA, who is one of the pre-eminent experts on California's vernal pools, and who was kind enough to guide me to some of the pools during my visit to the area.

The waters seemed to go on forever, and circumscribing its body was open grasslands and vibrantly colored wildflowers. It was a bright but somewhat overcast day, and the strong wind made the gold-tinged annual grasses dance and sing as I stood marveling at the amazing vernal pool that was Olcott Lake. I had come to Northern California in search of the rare and endangered Orcutt grasses, but right then all I could think about was how utterly beautiful the prairie was, and how grateful I was that people had the foresight to preserve such treasures.

Vernal pools are a type of wetland that are filled with water by rain or snow melt, but then dry up completely by summer. They have no permanent inlets or outlets, and the unique environment that they create is home to some of the rarest and most endangered plants and animals in the country.

|

| Dried vernal pool near Sacramento, CA, USA. The depression in the ground is a telltale mark of this habitat during the dry period. |

The existence of vernal pools depends on seasonal variations in precipitation, and a relatively impermeable layer of bedrock or hard clay that keeps the water from percolating down into the subsoil (see diagram below). During the winter and spring, rain water accumulates in the topmost soil layer, and creates pools where there are depressions in the surface. When summer comes, the pool dries out completely. This alternation of wet and dry states creates a habitat that is separate from the surrounding environs and home to rare endemics. The usual grassland and other plants (including invasive grasses) are drowned during the wet phase, and common wetland plants die out when the pool dries completely. Click here to learn more about the naturalized exotics and invasive plants that also inhabit vernal pool.

Vernal pools tend to exist as groups or complexes, with the pools sometimes connected to one another. From the air, the pools form a multi-colored spectacle, as shown in the video below.

One of the most endangered and rare inhabitants of vernal pools are the Orcutt grasses, which form the tribe Orcuttieae in the subfamily Chloridoideae. These grasses, as well as the other rare endemics that can survive only in vernal pools, are one reason why such habitats are so fascinating, and why they must be protected and cherished.

If there is a group in the Poaceae that could excite plant geeks, this would probably be it. The Orcutt grasses are unlike any other grasses out there, and their phylogenetic relationship to other members of the subfamily (and family) are still shrouded in mystery. There are nine species and three genera within the tribe: Orcuttia, Tuctoria, and Neostapfia, with Orcuttia being the most derived genera and Neostapfia being the most basal lineage. All the genera are monophyletic with the exception of Tuctoria (Boykin et al, 2010).

|

| Orcuttia viscida in Fair Oaks, CA, USA |

The Orcutt grasses are all endangered or threatened, and are endemic to vernal pools in California and Baja California. They are very short statured, and supposedly reach only 15 cm in height, although all the specimens I encountered in the field were 4 cm tall or less. I had to lie flat on my stomach in order to take straight macro shots of the specimens, a prime example of "belly botany."

These plants are also blessed with numerous foliage glands that make them strongly aromatic and viscid (sticky), traits which probably protect them from both herbivores and desiccation (Roalson, 1999). They do not look like any typical grass, and my first impression of them was how hairy and compact they looked. Even their leaves are atypical, with no separate sheaths and blades, and lacking ligules.

|

| O. viscida with inflorescence near Sacramento, CA, USA |

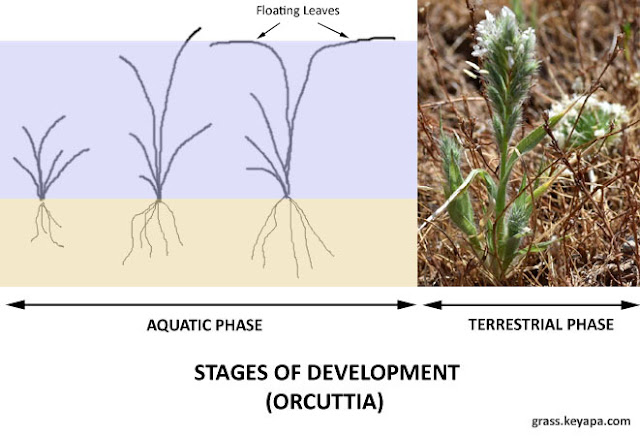

In addition to their rarity and physical attributes, the life cycle of Orcutt grasses is extremely fascinating (see figure below). The seeds lie dormant over the winter for as long as there is no water in the vernal pool, but once the rains come during spring they may germinate. However, they will only do so if there is a large enough body of water in the pool to support them. The growth of fungi around the seeds as organic matter decays in the pool is one way for the grass to tell that it is the right time to germinate, and so Orcutt grasses are dependent on such fungi for germination.

After germination, the new plant remains completely submerged in water for the first few months, using small aquatic leaves to photosynthesize. Even while underwater, Orcutt grasses use a type of photosynthesis called C4 photosynthesis. Studies show that the more derived Orcutt grasses (genus Orcuttia) lack the usual Krantz anatomy of C4 plants in their aquatic leaves, even though at one point people thought that this was an essential requirement for the process (Keeley, 1998). This is another unique feature that makes these grasses so amazing.

After about one month of being completely underwater, the grass develops two long narrow leaves that float to the surface of the slowly drying pool (see figure above), and this enables it to photosynthesize more efficiently. Finally, once the pool has completely dried up, the grass develops normal terrestrial leaves, and shortly thereafter produces flowerheads. As the summer progresses, any seeds that are produced are held tightly against the body of the desiccating plant, instead of being scattered far and wide. This behavioral adaptation is important because of the very limited number of vernal pools and their small area. In a sense, each vernal pool is like an island, and any seeds that are carried away from the safety of that island and onto normal ground will surely perish.

|

| Hairy flowerhead and anthers of O. viscida |

This ability of Orcutt grasses to be fully aquatic then fully terrestrial is remarkable, and studies have shown that the ancestors of this group were terrestrial. Over time, the group accumulated features that enabled them to survive in the extreme and changeable conditions in vernal pools. This evolution is reflected in the phylogeny of the species within the group. The more derived genus Orcuttia has aquatic adaptations such as the loss of stomata, floating leaves, and C4 photosynthesis without Krantz anatomy, features that are not found in the more basal genera Tuctoria and Neostapfia (Keeley, 1988).

|

| Orcuttia tenuis near Sacramento, CA |

.jpg) |

| Vernal pool faerie Shrimp (Branchinecta lynchi) by By Dwight Harvey USFWS |

|

| Vernal pool tadpole shrimp (Lepidurus packardi) by Bill Stagnaro |

|

| Inflorescence of Orcuttia tenuis near Sacramento, CA |

|

| Fenced vernal pool surrounded by apartments and parking lots in San Diego, CA, USA |

Vernal pools, like many other open environments, are victims of scale and human sensibilities. They are frequently located in open grasslands, and to hungry land developers, the seemingly "empty" area is a target to be turned into farms or paved over and filled with mini-malls and residential complexes and gas stations.

Vernal pools are also ephemeral in their beauty. They are filled with water and blooming plants only for a small part of the year. This means that for most of the time, the only thing that people can see when passing by a pool is a depression in the landscape that is almost devoid of vegetation. This ephemeral beauty is even more pronounced for vernal pools that are located in urban and suburban areas, where for most of the year they look like fenced-in empty lots.

|

| Cluster of O. viscida in Fair Oaks, CA |

Jepson Prairie Reserve in Dixon, CA is where the huge Olcott Lake is located. This 38 ha playa pool is amazing, with trails that wind around and next to the lake. It also has picnic areas and a nice parking lot. When I visited the place last month it was still filled with water, and so I could not find any Orcutt grasses (they would still be underwater at this stage), but the area was blanketed with tiny yellow flowers.

Phoenix Park in Fair Oaks, CA is another publicly accessible location with many smaller vernal pools. It is next to baseball fields and the other usual suburban park amenities, which makes it doubly easy to visit. The vernal pools are not as untouched as some of the out of the way ones I saw, but there was at least one cluster of Orcuttia viscida in the place.

|

| Phoenix Park Vernal Pools in Fair Oaks, CA, USA |

It should be noted that when it comes to vernal pools, timing is everything, and you should try to consult with local experts as to when it can be best viewed. In my case, I was more concerned about observing the Orcutt grasses, so pools with water still in them were not the best option. But other people might want to view the wild flowers that bloom in profusion, or want to see the animals that make the pools their home. In these cases, visiting when the pools still have some water would be the thing to do.

|

| Another pic of Olcott Lake at Jepson Prairie Reserve, Dixon, CA, USA |

|

| Newly-terrestrial O. viscida near Sacramento, CA, USA |

|

| Newly-terrestrial O. viscida with developing inflorescence near Sacramento, CA, USA |

|

| Orcuttia californica (?) that is newly terrestrial in San Diego area |

Literature Cited:

Boykin LM, Kubatko LS, Lowrey TK (2010). Comparison of methods for rooting phylogenetic trees: a case study using Orcuttieae (Poaceae: Chloridoideae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010 Mar;54(3):687-700. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2009.11.016. Epub 2009 Dec 6. PMID: 19931622.

Keeley, J. E. (1988). Anaerobiosis as a Stimulus to Germination in Two Vernal Pool Grasses. American Journal of Botany, 75(7), 1086–1089. https://doi.org/10.2307/2443777

Keeley, J. E. (1998). C4 Photosynthetic Modifications in the Evolutionary Transition from Land to Water in Aquatic Grasses. Oecologia, 116(1/2), 85–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4222061

Roalson, Eric H. (1999) "Glume absence in the Orcuttieae (Gramineae: Chloridoideae) and a hypothisis of intratribal relationships," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Floristic Botany: Vol. 18: Iss. 1, Article 17. Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol18/iss1/17

No comments:

Post a Comment